My editorial in the Stavanger newspaper

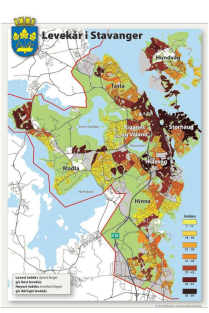

A week ago Stavanger’s newspaper, Aftenbladet, featured a two-page special section on schools in Stavanger. The article discussed the decision by the local government to give more money to schools categorized as having “the worst living conditions” in the city.

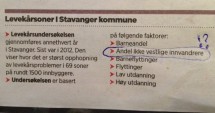

The small box in the lower left-hand corner of the infographic states that the lowest index (lightest colors) denotes the best living conditions, while the highest index (darkest colors) denotes the worst. Below this the newspaper informs that the survey, completed in 2012, was based on the following factors: percentage of children, percentage of non-Western immigrants…

And that is where I stopped, mouth open in a pre-scream. I immediately grabbed my phone, took a picture of the newspaper page, and posted it to my Facebook page with the comment: “Oh no you didn’t, Stavanger kommune!”

But I felt it wasn’t enough just to rant to all of my friends on Facebook, preaching the converted, as it were, and so I wrote an editorial for the newspaper which was published on Saturday . The English translation follows.

“Stavanger: Storhaug raises my living conditions”

When we moved to Stavanger from Bergen with our two young children we were not forced to live in Storhaug; we chose to live in Storhaug. I admit that I did not fall immediately in love with the area. Its run-down buildings seemed dreary, and I didn’t think there were enough trees, but I did appreciate that it was within walking distance to town. The fact that a large number of my colleagues at the University of Stavanger lived in Storhaug was also a good sign.

Our first week in Storhaug convinced us that we had made the right decision. We do not love Storhaug for its buildings but for its people: dark brown, light brown and various shades of pale. Storhaug is alive. It is a place with friendly neighbors, and not the type of area where people lock themselves up in their houses and don’t speak to others. I was angered, but also confused, by the categorization of Storhaug as having the poorest living conditions in Stavanger.

In his autobiography Nelson Mandela wrote, “No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.” It is absurd that in 2014 we are still categorizing people by their ethnicity and race, that it is still ok to make claims about what is “best” or “worst” based on skin color or ethnicity or nationality. But I am in agreement with Mandela that love comes more naturally to the human heart, and so I would rather share my love and gratitude for the people of Storhaug who raise my living conditions on a daily basis.

Thank you to my Pakistani neighbors for being among the first to stop by and say hello when we moved in. And thank you to your son for his kind smile when we pass in the morning on the way to school and work. Thank you to Sandra, an assistant at Storhaug school. My daughter adores you for your kindness and warmth. To the Romanian who lives next door to us with the Hollywood license plate and colorful flowers around his home: you once shouted to me with an enormous smile, “Music is LIFE!” Thank you for adding vibrance to our street and to our lives. Thank you to the Turkish shop owner who introduced me to the best yoghurt I have ever tasted. Thank you, too, for giving my daughter a chocolate. You made her feel special. I would also like to thank the Somalians who live behind us. In the evenings you sit outside and speak animatedly to one another, and although the stories you tell are not in a language I understand, your laughter reminds me that life can be good, even on tough days. Thanks to all who have moved here from near and far away and have chosen to share their lives with us in Storhaug.

It is true that I have only lived in Stavanger for six months, but my experience is that Stavanger is a wonderfully diverse, lively, cosmopolitan city, and Storhaug contributes to this. To the Municipality of Stavanger: I believe you owe an apology to the people who comprise your city, but I also believe you have a serious choice to make for the future. You can be a town of suspicion and fear that views people from other countries as a problem, or you can embrace your immigrant identity with excitement and love, recognizing that whether or not we have Norwegian citizenship, we immigrants are members of the Stavanger community who create the tapestry of culture, traditions and beliefs that is Stavanger.

I am pleased that the city government wants to give more money to the schools in the downtown area, but I want them to do it for real reasons such as poor results which show that students in those schools need extra help – students who are Western immigrants and ethnic Norwegians, too. And maybe if the criteria were changed a bit and intercultural education (something I value for my children) were considered, some of the schools out in Madla and Hinna would also need extra funding.

Assimilation Nation

During the summer, when this blog and everyone else was on holiday, Aftenposten, Norway’s largest daily national newspaper, published a cover story with the headline: “Født i Norge, føler seg som utlendinger” – “Born in Norway, Feel Like Foreigners”. The subtitle read: “Less than half of Oslo teens with foreign parents feel Norwegian. Even though they are born and raised in this country.”

I saved the newspaper, and a follow-up editorial, hoping to write my own response when I had time. The question nagging me was this: Why is it so important that we all feel Norwegian? And for whom is so it important?

Aftenposten asked the following three questions to the children of immigrants in Oslo:

- When do you feel Norwegian?

- When do you feel like a foreigner?

- What do you think is typically Norwegian?

None of those interviewed were of European or North American descent (see my post on not being an immigrant), but the questions bothered me more than the answers. Clearly one should either feel Norwegian or foreign. One or the other. But the children of parents born elsewhere aren’t either/or. They are both and neither.

The response of Ramyar Izadi (20), whose parents were born in Iran, speaks to this dilemma. To the first question he responded: “That’s a strange question. I feel Norwegian. I am Norwegian-Iranian. I live in Norway, most of my friends are Norwegian…”

While he might feel Norwegian, he refused to make an either/or distinction when it came to describing his identity: “I am Norwegian-Iranian.”

My ten-year-old son was only two when we moved to Norway and I asked him the three questions listed in Aftenposten. He replied that he feels Norwegian at school and foreign at home.

“But when your friends come to our house – what then?”

“I feel Norwegian. Unless you are trying to speak Norwegian to them. Then I feel foreign.”

Typical, I thought. But why?

“Because it’s so embarrassing!

Of course. Of course it is. Difference embarrasses us. But why? Who set the bar at perfect assimilation? At wearing a disguise so well that no one ever need know the truth until they see an unpronunciable last name?

The following day Aftenposten published a lengthy response from Inger Anne Olsen: “Velkommen til utenforskapet” – Welcome to Outside the Cupboard. (The word “utenforskapet” is used for those not included in the grand Norwegian “we” and has become politically charged in discussions of the disabled and unemployed).

Olsen writes:

Do you feel Norwegian? The question is fuzzy. (…) What does the one who asks this question really want to know? That I am loyal or disloyal? An enemy or a friend? Is it a well-meaning question with the purpose of finding out whether I feel integrated and included? Or is it a suspicious question, to have confirmation that I am different and foreign? (…) And why was I asked? Is it because I look different, dress differently, have a different skin color? Or do I have to answer for my parents’ ancestry?

At the heart of her response lies an even tougher question: “Is it important to feel Norwegian? MUST one choose between identities, and if so, why? Most of us carry many identities within ourselves. By requiring an answer to this type of question, we are forcing people to negate some of their selves.”

The phrase to negate some of their selves rang in my ears. Craving assimilation while being unwilling or unable to shed enough of myself to be Norwegian. It’s an unsolvable dilemma, not only for the immigrant, but for the so-called ethnic Norwegian who fails to understand what words like assimilation and integration really require of both sides.

Headlines distinguishing between “Ethnic Norwegians” and people like Javad Mushtaq, of Pakistani heritage, yet born and raised in Norway, underline the either/or binary in red ink. (I return to the subtitle of the Aftenposten article: “Less than half of Oslo teens with foreign parents feel Norwegian. Even though they are born and raised in this country” and ask, is it any wonder?)

Olsen’s response reveals that the problem is not how well we assimilate or speak the language. It lies elsewhere, in an old late-18th century belief that nations are made of like people with like histories and like languages and like skin colors.

“What type of response would researchers have gotten if they had instead asked: ‘Are you happy in Norway?’” she wondered.

In an article on the citizenship in the 21st century in the “post-national” era, Isabel Estrada Carvalhais points to the fact that “social citizenship” is what actually matters in people’s lives. In other words, the extent to which non-nationals are free to participate in the community matters more than the color of their skin or the words on the cover of their passport.

Olsen’s question might then be phrased differently: Has Norway allowed you to be happy?

The spotlight turns from the immigrants interviewed by Aftenposten to reveal Norway, unaware that it might be called upon, hands over its face to block the sudden brightness of the light.

* The English translations of both Aftenposten articles are my own.

Morning walk

If I had never moved to Norway, would I have learned to walk? To walk without a destination, to walk without a watch and something I must hurry home to do, to walk without headphones or a steady aerobic pace, to walk and be still. So still that I can hear the tongues of sheep slopping mouthfuls of grass between their teeth. So still that I notice when a leaf falls to the ground, tickling others leaves as it floats through the branches. So still that when I slide on a mossy stone and “Woah!” slips out of my throat, I feel embarrassed by the intrusion my noise makes into this quiet sleep of a world.

And when the dirt path turns to gravel and tumbles to a stop at Salhusveien, my world is pierced by the boisterous laughter of school children, and the loud deep rumble of a recycling truck as it changes gears, and the music escaping from a passing jogger’s headphones. But I pull my arms inward and remember how, just minutes earlier, I turned around and caught the sun winking at me through the yellowing leaves of a rowanberry tree.

I inhale gratitude and walk home.

L’Italia

‘The other ambassadors warn me of famines, extortions, conspiracies, or else they inform me of newly discovered turquoise mines, or advantageous prices in marten furs, suggestions for applying damascened blades. And you?’ the Great Khan asked Polo. ‘You return from lands equally distant and you can tell me only the thoughts that come to a man who sits on his doorstep at evening to enjoy the cool air. What is the use, then of all your traveling?’ Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino.

You arrive at a city called Napoli where the trash is piled as high as your shoulder. Organized crime is to blame, they tell you. Dead birds litter the street and vile-looking dogs skimp about between the zips of mopeds carrying women who clutch babies in one arm and their boyfriend’s back with the other. The streets of Napoli are so black that on narrow streets you must look up to be sure of the sun’s existence. No one looks before crossing these streets, where a discordant symphony of cars and people and mopeds and elderly women dragging shopping trolleys behind them plays in endless repetitions. In Napoli, everyone, everywhere is involved in the fiercest argument you have ever seen, acted out in intense pantomimes. The old men sit on benches in front of shops that sell long, tight rolls of pink sausages, waiting for someone to join them, and the young girls run by in high heels outlined in diamantes.

In Napoli, a city spilling its ugliness right out to the sea, you will also eat the best pizza you have ever tasted and you will vow never to leave this city of traffic exhaust, garbage, and shouting men. The crust is more like naan bread, you think, and it is topped with a sauce so sweet and rich that you begin to ponder on climate and soil types and family secrets because you know this taste cannot be reproduced anywhere else in the world. You will dream of abandoning your family, selling your possessions and signing up for a course at the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana – the True Neopolitan Pizza Association – to become a pizziola. This is the effect of Napoli, the birthplace of pizza and chaos: it is a city of repulsion and desire.

You will dream of abandoning your family, selling your possessions and signing up for a course at the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana – the True Neopolitan Pizza Association – to become a pizziola. This is the effect of Napoli, the birthplace of pizza and chaos: it is a city of repulsion and desire.

When you have traveled for five hours from this city, heading north and northeast, you will come to another sea, one lined with perfect cliffs just like the ones you have seen on postcards from exotic places. Its beaches are made of stones so smooth you will lie down on them and feel as though you are swimming in sand. You will fill your backpack with them and insist on carrying them through two airports and all the way back home. At home you will arrange them carefully on a ceramic plate under your window so that you can see them and touch them and be reminded of what it was like to lie on that beach in the pink light of early evening, when smiles appeared without even a thought to precipitate them.

There along the Adriatic, in a town called Sirolo that was built along the beach before the sea became a thing of pleasure, are family-owned beach huts that look like a long row of garages. Painted in pale blues, pinks, and greens, they mark the spot where generation after generation has come to fish and cook their catches. One of them is open and you dare to peek inside where at first you see nothing but a picnic table and a camping stove and an orange and brown bead portieres. Looking more closely you notice a pasta strainer hanging from the wall, and next to it a framed, black-and-white photo of il nonno. This is a place painted so thick with tradition it threatens to smother you, but you are still envious.

There along the Adriatic, in a town called Sirolo that was built along the beach before the sea became a thing of pleasure, are family-owned beach huts that look like a long row of garages. Painted in pale blues, pinks, and greens, they mark the spot where generation after generation has come to fish and cook their catches. One of them is open and you dare to peek inside where at first you see nothing but a picnic table and a camping stove and an orange and brown bead portieres. Looking more closely you notice a pasta strainer hanging from the wall, and next to it a framed, black-and-white photo of il nonno. This is a place painted so thick with tradition it threatens to smother you, but you are still envious.

By now you know that the special quality of Italy is to be fabulous even when it isn’t: a carpet of ants blackened the floor of the bathroom in your hostel in Pompeii; bees came to drink at the Tuscan farmhouse where you spent a week, and then hid in the grass from unsuspecting bare feet; in the hills outside of Perugia draught and water shortages offered a choice between flushing the toilet or showering just long enough to get wet.

All sins are forgotten, however, when holding a glass of wine made from grapes that grew just at the edge of the garden where you now sit. In the newly darkened sky you gaze at the golden glow of Montepulciano, rising above the vineyards like a crown on a king’s head. You suspect that it cannot be just good wine and good food and good weather that has enamored you with this country. Other countries offer these joys as well. What exactly is is, though, remains Italy’s secret.

Avrai tu l’universo, resti l’Italia a me. “You may have the universe, if I may have Italy,” wrote Guiseppe Verdi.

In the space of one breath – for that is all it takes – you realize that Italy is the country of all your dreams, both past and future. You know you will travel again, take new vacations to new places, or maybe even return to this very spot next summer. You will always be searching for a way back, not to this place, but to this moment.

My Turtle House

I sit outside to read in the hopes that I can gather up enough rays of sun to last through next week when the newspaper predicts the return of the rain from its sommerferie (apparently spent in Oslo).

I let my papers fall to my lap and close my eyes, though the sun still shines white through my eyelids. An out-of-sync tune is hammered out by birds overhead, a lawnmower purrs away down the street.

Without even a thought to take me there, I am suddenly lying on a beach towel on the wide green lawn at the house on Pheasant Run (where I did some of my growing up). The sound of our lawnmower approaches and then leaves again as my dad walks in neat diagonal stripes. I am lying so still that a squirrel dares to come within a foot of my blanket. I am the first to be frightened, and the sudden flick of my legs sends the squirrel sprinting.

It occurs to me that I haven’t stored my memories dutifully like the events in my diary, nor can I string them out into a straight line like the days on the calendar. They follow their own system of organization, determined not by when but by where. Where was I then? (And the answer unlocks a room so large I that I can live in it for a good long while.)

I have transported this network of memories with me through Costa Rica, Tunisia, Singapore, England, Canada . . . borne on my back like a turtle’s shell that I’ve dragged along with slow, thick legs. And with a turtle’s obstinacy, I remain oblivious to the fact that this “home” I’m always looking for isn’t where I’m headed, but just there, right behind me.

Wanderlust

This blog took an unintended vacation. End-of-term grading, a two-week visit by my parents, most of the country on strike, and the sun came out – and stayed out all night! And it felt good to not think and just be. So that is what I did.

Sindbad the Sailor set out from his home of Baghdad, “the Abobe of Peace,” because of the words of a poet:

A man must labor hard to scale the heights,

And to seek greatness must spend sleepless nights,

And to find pearls must plunge into the sea

And so attains good fortune and eminent be.

[. . . ]

On his first voyage Sindbad witnesses horses leaping from the sea, finds a fish four-hundred feet long, meets a generous king, and attains great wealth before heading back to the port town of Basra and then on to Baghdad. At home he visits with his family and friends for a short time before the tug of wanderlust yanks on his shirt again.

“I lived a most enjoyable life of unalloyed pleasure until it occurred to me one day to travel abroad, and I felt a longing for trading, seeing other countries and islands, and making a profit.” So begins Sindbad’s second voyage.

The wonders and adventures increase as the story moves along, each journey taking Sindbad to what he believes will be his death, only to end in miraculous rescue. He escapes cannibals and man-eating apes, is trapped in a valley of snakes so large they can eat elephants, becomes enslaved by the Old Man of the Sea, and is ship-wrecked – he is always ship-wrecked. And desolate. And crying out to God.

Sindbad always returns safely home, but he always wants to leave home again. This sailor doesn’t suffer homesickness, but awaysickness. Before his third voyage Sindbad confesses his addiction: “I lived in Baghdad for some time, in prosperity and peace and happiness, until my soul began to long for travel and sightseeing and commerce and profit, and the soul is naturally prone to evil.”

Sindbad blames his evil soul for his ache to be away, and his returns home become nothing more than the impetus to send him off again. Home, away, home, away, home, away, each place defining the other, until one day he decides he has had enough. Sindbad vows to God that he will never travel again by land or sea.

Were the twenty-seven years Sindbad spent on his seventh and final voyage too long? Had his soul simply grown too tired to lure him into adventure again?

“How much toil and trouble I endured in the beginning!” Sindbad tells his porter before beginning his storytelling. Even so, he is quick to add: “Each voyage is a wonderful tale . . .”

Here’s to a life of wonderful tales, of being awaysick, and of always finding your way home when you need to.

Expat Blog

On Friday night my son and I sat on the sofa watching Snake Crusader with Bruce George on Animal Planet. Bruce George is a licensed snake handler who lives in Australia and rescues all sorts of horrifyingly large, deadly or otherwise stomach-turning snakes from roadsides and the drawers of messy teens. (“You’d better keep that room clean, young man!” he threatens in his Aussie accent while pulling a long thin snake from a slightly open drawer. “Just think about a death adder coming to get you in the middle of the night!”) Bruce George is my son’s hero and he has pictures of him tacked to the wall beside his bed.

“Maybe you should live in Australia,” I say to him, knowing that the tiny adders that live in Norway aren’t interesting enough to keep him here.

“Nah. I’m not going to live anywhere,” he tells me. “I’m just going to travel.”

Of course! I thought. An appropriate response from the son of two “home”-less people like my husband and me. Even if the life of traveling doesn’t turn out to be as glamorous as he thinks it is now, it reminded me of how free we 21st-century people feel to roam the world (as long as “home” and “money” aren’t a problem, of course).

Which brings me to the point of this post – the thousands of people worldwide who are using internet forums to peruse and perhaps find new places to throw some luggage down for a few months, or maybe even permanently.

I can’t remember how I first came across “Expat Blog” – the site linked to by the little, happy blue suitcase in the right margin of this blog. Maybe I googled “blogs Norway” or “people with confused identities,” but it led me to a world of people who, just like me, were in love with other cultures and seeing the world, and who wanted to share the daily joys and struggles of being an expat.

Expat Blog was launched in 2005 as a site for expatriates (current, future and past) and the site now boasts 420,000 members from 206 countries and 400 large cities. Not all of these people writes blogs, of course. Some are just looking for answers on how to move, where to find work, or want to find people with whom they can share experiences. Expat Blog has discussion forums, a blog directory, guides, photo albums, a business directory, a classifieds section, and they have just introduced a new “jobs” and “housing” section.

If you are looking for work in Norway, no matter where you are in the world, you have access to the Norway job opportunities section where you can search by category or type of contract. If you are looking for a place to live, the new accommodation in Norway section offers places to rent, buy, or share. (Note to those currently living in Norway: you can also post ads here!)

A large number of my readers find my blog each week through Expat Blog, and the site has also allowed me to meet and connect with a whole new group of blogging friends.

Whether you are an expat or soon-to-be-expat, or just interested in what it’s like to live in Iceland, Samoa, or Chile, or just about anywhere, I invite you to check out Expat Blog. You might even find you have a lot to chat about with others who don’t exactly live anywhere.

Vi ♡ Norge

“Don’t you hate it when …?” … “Have you seen how they?” …. “Why can’t they be more ….” “Why are they so ….”

We immigrants love to do this sort of thing. It makes us feel like we’re not crazy for thinking a certain custom/tradition/behavior/response is the most ridiculous thing we’ve ever seen. “This place would be so fabulous,” we say, “if only it could be a bit more like America or Holland or Tanzania. Then it would be the most perfect place on earth.” (Never mind that it would no longer be Norway.)

We readily admit to our love/hate relationship with Norway, which really isn’t so different from the frustration a wife feels for her husband when he loads the dishwasher all wrong, or doesn’t notice the toilet needs cleaning, or puts her bras in the dryer. I love all the wonderful things about you dear, but, you see, my way is just, well, the right way to do it.

But we immigrants also love to sit around and share what we love about Norway, because it reminds us of why we came here in the first place, or at any rate, why, despite continuous rain and painfully high prices, we stay.

Norway: in honor of 17 May, Norway’s National Day, here is a list of everything I love about you, everything you do just perfectly:

Photo: Bergen Tourist Board/Per Eide.

- fresh shrimp from the sea, cooked on the boat and sold at the fisketorget in Bergen

- the brick-colored sky when the sun hovers just under the top of the mountains

- the secretive blue world of late morning light in winter

- forking trails that invite me to never reach my goal

- the tradition of Sunday hikes

- chemical-free drinking water

- Hvitveis and Blåveis, carpeting the forests in spring

- the crisp and cozy smell of sheets dried outside in the sea air

- the word “kos” and for worshipping it when we need it more – in winter!

- tursjokolade

- that children are safe to run free and explore their world

- dagpenger and sykemeldinger for those who need it

- equal access for everyone to health care

- free education

- kransekake

- civil rights for everyone, even in same sex marriages

- the importance of “we”

- the explosion of wild berries in the woods, along the roads, and in our backyard in August

- the light of the midnight sun, even when it’s raining

- roundabouts

- Christmas and Santa Lucia Day

- påskekrim

- chili nuts

- feriepenger and half-taxes in June and December

- a workday that ends at 4 p.m.

- the value placed on families

- barnehage — a paradise for all 6 and under!

Please feel free to add to my list in the comments below!

To read last year’s post on the traditions of 17 May, click here.

“We get the country we pay for”

When fellow American blogger Teresa Owens recently spent two months in Norway she commented — or rather sighed: “We get the country we pay for.”

Given that yesterday the State of the World’s Mothers Report awarded Norway with first place (for the third year in a row), I resurrect one of my favorite “Daily Show” pieces: The Stockholm Syndrome, from 2009. The Daily Show sent comedian and reporter Wyatt Cenac to Sweden in the hopes of waking the Swedes up from their “socialist nightmare.” It’s a hilarious look at the world of democratic socialism from, well, the eyes of a capitalist.

The video is in two parts and if you are in a hurry you can begin part 1 at 1:45. (And yes, it’s about Sweden, but we know the only real difference between Sweden and Norway is the vowels and the meatball recipes).

Vodpod videos no longer available.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

The U.S. was ranked 25th in the list of best places to be a mom, far below many other “first world” nations. I’m not Norwegian, so I cannot boast about this ranking, nor even the many other “best in the world” achievements that Norway has earned, but I do want to be proud of my own country. I grew up believing it was the best in the world, and maybe at one time it was.

Dealing with Anders Behring Breivik

I sat down on the sofa last night with my copy of Aftenposten, turning the pages in hopes of finding something to read that wasn’t about Anders Behring Breivik, or, paradoxically, the surge of immigrants coming to Norway (an increase in 41% from 2005-2009).

“Vanskelig å diagnostisere Behring Breivik” (“Difficult to Diagnose Behring Breivik”) read a headline that I flipped past, and then, with agitation returned to.

My husband sat next to me on the sofa, peering intently into his iPhone. “Are you concentrating on something?” I asked him. “Or can I tell you what I’m thinking?”

I do this often: use him as a sounding board. He knows that most of the time he is just supposed to listen to me rant, but I know I can trust him to tell me when my ideas have gone completely off the deep end, or when I actually might be onto something.

“Is it possible that we just want to believe Breivik is nuts so that we don’t have to listen to him? Maybe that’s why he is difficult to diagnose. Maybe there isn’t anything wrong with him psychologically.”

I was thinking of Foucault’s theory that societies need to categorize people into normal and abnormal to gain power and control; thus, as a society we decide that certain behaviors are psychoses (for more, read Foucault’s Discipline and Punish.) In other words, it serves a particular social purpose to believe that Breivik is crazy, because then we can say: he is not like us. It is much harder to believe that he is sane and could actually kill people for his beliefs. Then we might have to take what he says seriously.

“The guys is nuts,” Aidan responded. “I mean, look, he has deluded himself into believing it was right to kill lots of people.”

“What about the army, then? Soldiers believe it’s right to kill for ideological reasons.” We argued back and forth about this point. I began to believe in neither my arguments, nor those of my husband, which happens often.

Ending the debate with a deep sigh, I shook the pages of my newspaper back into a readable form, and found myself intensely engaged in the court transcripts of Breivik’s interrogation yesterday. No more than ten lines in, I reported to Aidan that I changed my mind: “He’s completely bonkers.”

It doesn’t take a psychologist to see that Breivik lives in a world completely disengaged from reality, a world in which he believes his arguments make such perfect sense, are so logical, that he could surely convince the rest of us of them if only given a platform.

Breivik described to the court his disgust at having to walk through the piles of dead bodies that he himself was responsible for: “I have never experienced anything so gruesome,” he claimed.

He spoke with eerie matter-of-factness about how he tricked a group of youth into believing that he was a police officer:

“It was actually just a coincidence that I saw a head sticking up from behind the pump house. And I realized that there were many people [hiding] there . . . I think I began with: ‘Have you seen him? Do you know where the shots came from?’ And then there were some who pointed in one direction. It was to lure them out so that I could execute them . . . I said there was a boat that would take them safely away, that they must come out now . . . They seemed very skeptical. But there were some, two or three of them, who seemed very relieved. I said: ‘You must come now.” And then there were three who came to me.”

Breivik shot and killed fourteen people at that particular spot on the island.

When asked by the prosecutor whether he had any feelings for his victims, Breivik responded, “I know what I have done . . . but one must remember that I, too, lost my whole family on 22 July, I lost all my friends.”

As spell-binding as statements like this are for giving us insight into the mind of a mass murderer, they divert us from Breivik’s message – a message the government and the press are intentionally suppressing by not televising the trial, and choosing what to print in the papers. After all, Brievik did say that the killings were only the first part of his campaign; he hoped the trial would comprise his propaganda phase.

But what would happen if we actually listened to Breivik’s message, if we could filter out his god complex and listen to the core of what he is trying to say? Would we agree with him that multiculturalism doesn’t work, or at least not in the “let’s all be happy about difference and just get along” way? Would we, too, want to protect Norway from the change that necessarily comes with an increasing immigrant community? (And would anyone dare to agree with Breivik and join the exiled ranks of Fjordman or certain hounded and now back-peddling members of the FrP?)

Norwegians do have very good reasons to be proud of their country, and there is much here that should be protected. Norway consistently ranks first in world indexes of prosperity, wellness, and human development; the Global Peace Index ranked it as the most peaceful country in the world; it is the world’s fourth wealthiest (GDP per capita), and its government has the world’s largest pension fund.

Norway works. It works exceptionally well. But Breivik knows there is more to it than that: Norway works, as long as everyone agrees to be Norwegian.

What does it mean when a country refuses to join the EU and taxes imported cheese to protect its farmers and encourage the purchase of local variants like Nor-gonzola? What views about being “non-Norwegian” are there when, during a butter crisis, people stew for weeks about whether they could/should/would opt for importing foreign butter, or would simply prefer to go without? (And when the foreign butter did arrive, large numbers refused to buy it.) What underlying values are at play when social integration into the culture of Norway is deemed the highest goal, more important, in fact, than learning to read and write in the first grade?

Breivik claims he was acting to protect his nation of Norway from multiculturalism, from immigrants, from foreign influence. Is it possible, then, that he simply took to extremes the very values that define what it means to be Norwegian?

Might there be good reasons to be critical of multiculturalism and immigration? Might there be good reasons to cling to the country we have now and fear the country it might become in the future? Globalization has coerced us into viewing the world in terms of flux, flow, open borders, dismantled barriers; we are one world, we are citizens of the world. But which of us actually lives as though we can float, problem free, from culture to culture, without ever feeling the blisters from the ill fit?

After I wrote the post titled “Normal,” I was surprised at how many readers resonated with a need for having things just the way they want them to be. We actually like our normal and predictable lives. Is it taboo to believe that in this tiny way we understand Breivik?

[A final note: Because Breivik has wounded Norway so deeply, I feel I must add that I in no way sympathize with Breivik’s thoughts or actions. In this post I merely intended to raise questions about the paradox between being a protectionist nation with strongly-felt patriotism that at the same time points a chastising finger to those with anti-immigration sentiments. I wonder where globalization will ultimately lead us and if it will ever be possible to exist in a world without nations or citizenship. As always, I welcome comments and criticism!]